Canine Lymphoma

What is lymphoma?

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymph nodes and lymphatic system. This cancer may be localized to one particular region, or may spread throughout the entire body.

The lymphatic system includes the lymph nodes, specialized lymphatic organs such as the spleen and tonsils, and the lymphatic vessels. Together, these components of the lymphatic system carry out a number of important roles in the body, including the movement of fluids and other substances through the body, as well carrying out immune functions in response to toxins or infections.

Is lymphoma common in dogs?

Lymphoma is a relatively common cancer, accounting for 15-20% of new cancer diagnoses in dogs. It is most common in middle-aged and older dogs, and some breeds are predisposed. Golden Retrievers, Boxer Dogs, Bullmastiffs, Basset Hounds, Saint Bernards, Scottish Terriers, Airedale Terriers, and Bulldogs all appear to be at increased risk of developing lymphoma. This suggests that there may be a genetic component to lymphoma, although this has not been confirmed.

There are four different types of lymphoma in dogs, varying in severity and prognosis.

- Multicentric (systemic) lymphoma.This is, by far, the most common type of canine lymphoma. Multicentric lymphoma accounts for approximately 80-85% of cases of lymphoma in dogs. In multicentric lymphoma, lymph nodes throughout the body are affected.

- Alimentary lymphoma.This term is used to describe lymphoma that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Alimentary lymphoma is the second most common type of lymphoma.

- Mediastinal lymphoma.In this rare form of lymphoma. Lymphoid organs in the chest (such as the lymph nodes or the thymus) are affected.

- Extranodal lymphoma.This type of lymphoma targets a specific organ outside of the lymphatic system. Extranodal lymphoma is rare, but may develop in the skin, eyes, kidney, lung, or nervous system.

What are the clinical signs of lymphoma?

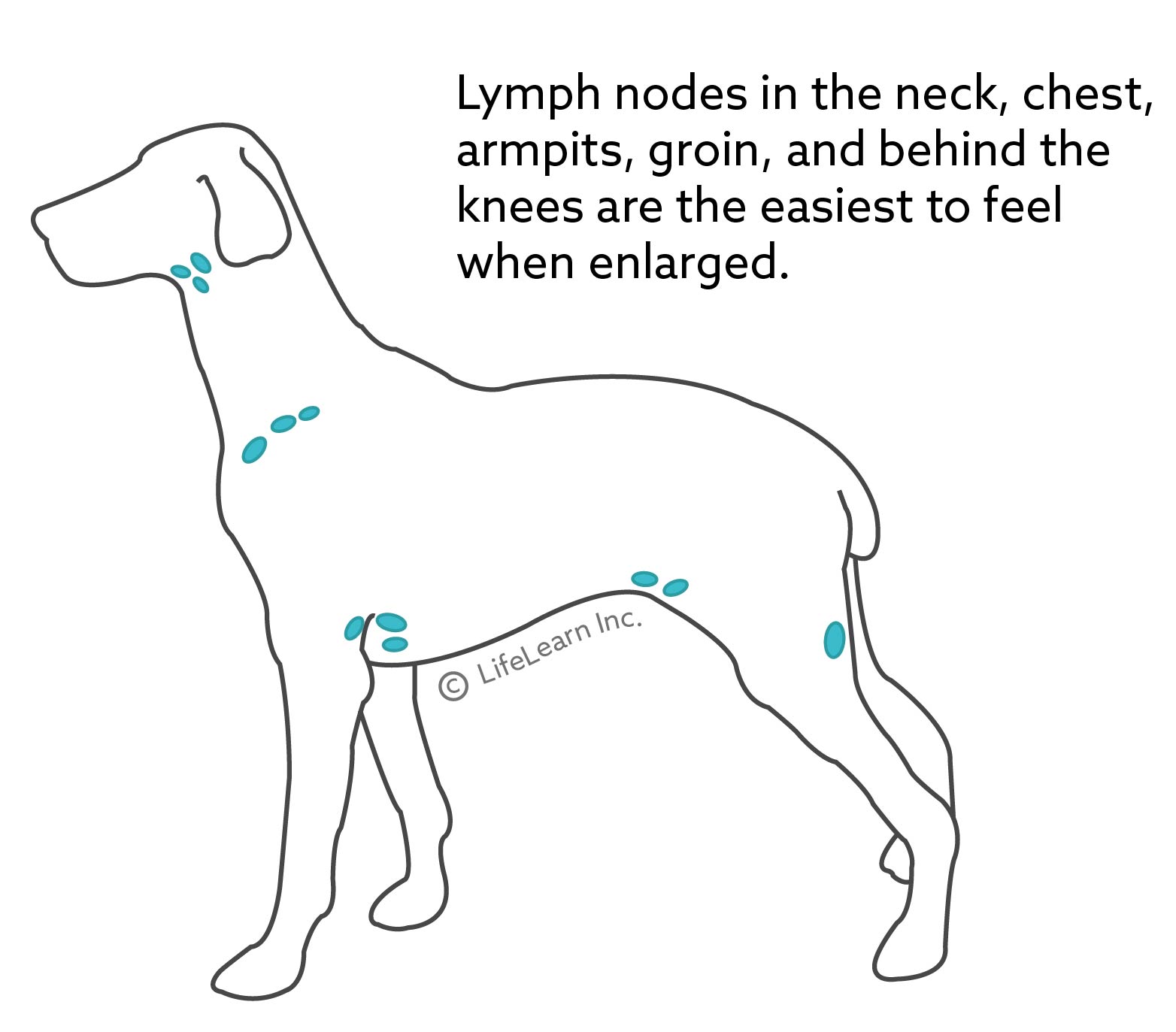

In dogs with multicentric (systemic) lymphoma, the first sign of lymphoma is swelling of the lymph nodes. The lymph nodes located in the neck, chest, armpits, groin, and behind the knees are often the most visible and easy to observe. Swelling of these lymph nodes may be noted by the dog’s owner, or first noted by the veterinarian on a routine physical exam. Most of these dogs do not have any clinical signs of illness at the time of diagnosis, although they will often go on to develop signs such as weight loss and lethargy if untreated.

In the other, less common forms of lymphoma, clinical signs depend on the organ that is affected. Alimentary lymphoma causes gastrointestinal lesions, resulting in vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss. Mediastinal lymphoma creates lesions within the chest that take up space in the chest cavity, commonly resulting in coughing and shortness of breath. The effects of extranodal lymphoma vary significantly, depending on the organ involved.

How is lymphoma diagnosed?

Not all dogs with enlarged lymph nodes have lymphoma. Enlarged lymph nodes may also occur due to infections or autoimmune diseases, so your veterinarian will perform tests to determine the cause of your dog’s clinical signs.The most common test used in the diagnosis of lymphoma is a fine needle aspirate. In this test, a veterinarian inserts a needle into an enlarged lymph node (or other organ) and removes a small number of cells. These cells are then examined under a microscope, looking for evidence of cancerous cells that indicate lymphoma.

If a fine needle aspirate is inconclusive, or impractical to perform due to the location of the lesion, your veterinarian may perform a biopsy. This involves the surgical removal of a tissue sample from the lymph node or lesion. This sample will be processed and examined under a microscope, looking for the presence of lymphoma.

Your veterinarian will also likely perform baseline screening bloodwork to assess your dog’s overall health. There are two components to this bloodwork. A complete blood cell count involves an examination of the cell types within your dog’s blood, assessing quantities of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. A serum biochemistry is used to assess the function of your dog’s internal organs.

If your dog is diagnosed with lymphoma, your veterinarian may perform additional testing to find out more information about the lymphoma and develop a treatment plan. These additional tests may include:

- This test uses specialized stains to distinguish between two different types of lymphoma: B-cell lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma. Identifying whether your dog’s lymphoma is B-cell or T-cell lymphoma can provide information regarding prognosis.

- Flow cytometry. This is another test that can be used to distinguish B-cell from T-cell lymphoma.

Your veterinarian may also recommend additional tests to determine the extent of your dog’s lymphoma. This testing most commonly includes the use of imaging such as X-rays or ultrasound.

There are five stages of lymphoma. Stage I and II are rarely seen in dogs, while Stages III-V are more common.

- Stage I: involves only a single lymph node

- Stage II: involves lymph nodes on only one side of the diaphragm (only affects the front of the body or rear of the body)

- Stage III: generalized lymph node involvement

- Stage IV: involves liver and/or spleen

- Stage V: involves bone marrow, nervous system, or other unusual location

How is lymphoma treated?

Lymphoma is treated with chemotherapy. There are a variety of procedures used, but most consist of a variety of injections given on a weekly basis. Fortunately, dogs tend to tolerate chemotherapy better than humans; they rarely lose their hair or seem to feel significantly ill during chemotherapy. The most common side effects of chemotherapy include vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased appetite, though even these effects are not seen in all dogs.

Surgery and/or radiation may be appropriate for certain types of low-grade localized lymphoma, but most cases cannot be successfully treated with surgery or radiation.

If chemotherapy is not an option, due to patient factors or owner financial constraints, prednisone can be used for palliative care. Although prednisone does not treat lymphoma, it can provide a temporary reduction in clinical signs and buy the pet some time.

What is the prognosis for lymphoma?

The prognosis for lymphoma varies, depending on various characteristics that can only be determined by specialized testing.

On average, dogs who receive no treatment (or who are treated with prednisone alone) have an expected survival of 4-6 weeks. This is an average, however, with some dogs being euthanized or dying before the four week point and some dogs living past six weeks.

With chemotherapy, lymphoma can often be put into remission. While lymphoma is never truly ‘cured’, remission is a term that is used to describe the temporary resolution of all signs of lymphoma. The average remission with chemotherapy is 8-9 months, with an average survival time of approximately one year with chemotherapy. Again, this is only an average; some dogs will die sooner and some will live longer than one year. Your veterinarian may be able to provide more specific information on your pet’s prognosis if you pursue additional testing to better characterize the lymphoma.