Neurological Assessment

What is epilepsy?

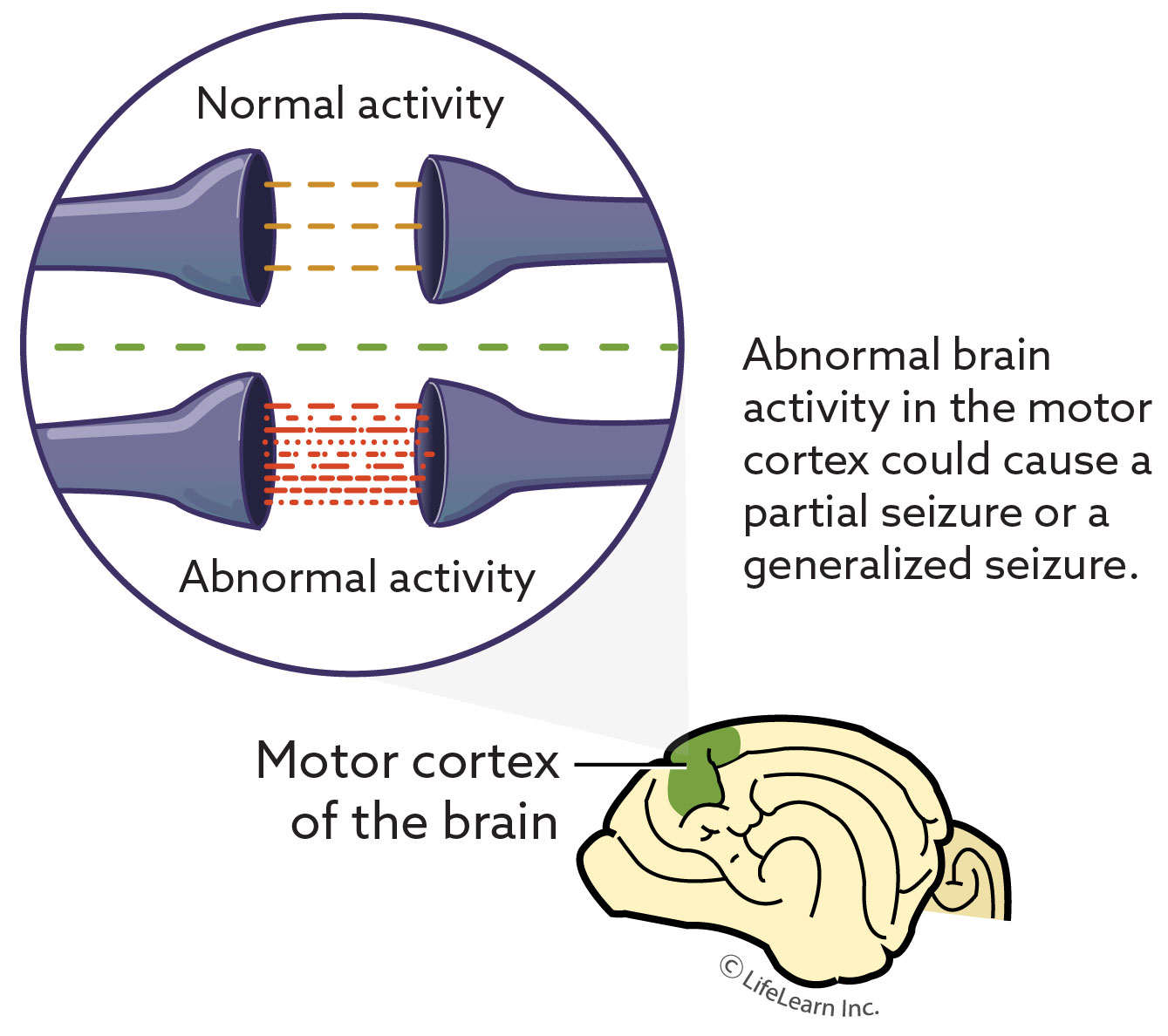

Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by recurrent seizures without a known cause or abnormal brain lesion (brain injury or disease). In other words, the brain appears to be normal but functions abnormally. A seizure is a sudden surge in the electrical activity of the brain causing signs such as twitching, shaking, tremors, convulsions, and/or spasms.What causes epilepsy?

The exact cause of epilepsy is unknown, but a genetic basis is suspected in many breeds.

Dog Breeds that have a higher rate of epilepsy include Beagles, Bernese Mountain Dogs, Border Collies, Boxer Dogs,

Cocker Spaniels, Collies, Dachshunds, Golden Retrievers, Irish Setters, Irish Wolfhounds, Keeshonds, Labrador Retrievers, Poodles, St. Bernards, Shepherds, Shetland Sheepdogs, Siberian Huskies, Springer Spaniels, Welsh Corgis, and Wire-Haired Fox Terriers.

Epilepsy is somewhat common in dogs and rare in cats.

What are the clinical signs of epilepsy?

Seizures can vary in appearance and can be focalized (only affecting part of the body) or generalized (affecting the whole body.

Focal seizures affect a localized region of the brain and therefore only has limited effects on the body. These effects may vary significantly, depending on which portion of the brain is affected. “Fly-biting” seizures are a specific type where the pet snaps at the air like it is biting at invisible flies. During these episodes, patients typically remain aware of their external environment. In many cases, they can even be distracted from these episodes by their owners.

Generalized seizures are more common and are often characterized by a stiffening of the neck and legs, stumbling and falling over, uncontrollable chewing, drooling, paddling of the limbs, loss of bladder control, defecating, vocalizing, and violent shaking and trembling. Seizures can last a few seconds to a few minutes, on average about 30-90 seconds, and the pet is typically unaware of the surroundings during this period.

Afterwards, the pet may appear confused, disoriented, dazed, or sleepy; this is called the post-ictal period.

Prior to the seizure, many pets will also experience the aura stage; this is characterized by the pet appearing anxious, frightened, or dazed, as if the pet can sense an upcoming seizure. It is estimated that up to two percent of all dogs will have a seizure in their lifetime.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

Epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion; the diagnosis of epilepsy is made only after all other causes of seizures have been ruled out. A thorough medical history and physical examination are performed, followed by diagnostic testing such as blood and urine tests and radiographs (X-rays). Additional tests such as bile acids, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be recommended, depending on the initial test results.

What is the treatment of epilepsy?

Anticonvulsants (anti-seizure medications) are the treatment of choice for epilepsy. There are several commonly used anticonvulsants, and once treatment is started, it will likely be continued for life. Stopping these medications suddenly can cause seizures.

The risk and severity of future seizures may be worsened by stopping and re- starting anticonvulsant drugs. Therefore, anticonvulsant treatment is only prescribed if one of the following criteria is met:

- More than one seizure a month: You will need to record the date, time, length, and severity of all episodes in order to determine medication necessity and response to treatment.

- Clusters of seizures: If your pet has groups or 'clusters' of seizures, (one seizure following another within a very short period of time), the condition may progress to status epilepticus, a life-threatening condition characterized by a constant, unending seizure that may last for hours. Status epilepticus is a medical emergency.

- Grand mal or severe seizures: Prolonged or extremely violent seizure episodes. These may worsen over time without treatment.

Phenobarbital is a common anti-seizure medication used in dogs, and is usually given twice daily. Irregular dosing schedules (including starting and then stopping the medication, or forgetting to give pills causing blood levels to fluctuate) may predispose your pet to more frequent or more violent seizures, so it is important to give the medication on time.

When starting this medication, phenobarbital levels are measured via blood samples every two to four weeks until the correct dosage is determined. Once the therapeutic dose for your pet is determined, phenobarbital blood levels and liver function tests will need to be monitored at least every six months to ensure that phenobarbital levels stay within the therapeutic range (i.e., that they do not get dangerously high or low), and that there are no signs of liver problems. In the event that phenobarbital blood levels get too high, liver failure can develop, which may lead to death. If the levels are too low, seizures will not be controlled.

Additional drugs such as potassium bromide or newer human anti-seizure medications such as zonisamide (brand name Zonegran®) or levetiracetam (brand name Keppra®) may be used. Your veterinarian will determine the proper treatment plan for your pet's condition.