Perineal Hernia

What is a perineal hernia?

The perineum, also known as the pelvic floor in humans, is the area between the anus and the scrotum or vulva. This area supports the organs of the pelvis. A perineal hernia occurs when there is a weakening or traumatic tear in the muscles of the area, resulting in the bladder, intestines, or fat pushing through the muscle to an abnormal position just under the skin. Perineal hernias are most common in middle-aged or older unneutered male dogs and occur rarely in cats and female dogs.

What are the clinical signs of a perineal hernia?

A perineal hernia may appear as swelling on either or both sides of your dog’s anus. Depending on how much tissue is herniated, it may even push the rectum to one side. The swelling is usually soft and can be reduced with pressure.

Dogs with perineal hernias often repeatedly strain as if to defecate, they may have difficulty passing stools and may become constipated. If the bladder has become herniated, they may also strain to urinate, have urinary incontinence, or be unable to urinate. In severe cases, such as when the intestine has herniated or if bladder herniation has caused a urinary obstruction, dogs will become lethargic and have a decreased appetite. Any compromise to the blood supply of the bladder or intestine could be life-threatening.

Why did my dog get a perineal hernia?

Although trauma can cause hernias, the more common cause is gradual muscle weakness in the area. The reason for this weakness is not completely understood but is believed to be associated with the following factors:

- As male dogs appear more affected, hormones are believed to play a role in hernia development

- Disruption of nerve function in the area, such as can be seen in dogs with spinal injuries

- Excessive straining can also lead to muscle weakness and herniation

What diagnostic tests will be performed?

Your veterinarian may be able to palpate the perineal hernia or an abnormal pocket in the rectum during a rectal examination. Baseline diagnostics, including a complete blood count , serum biochemistry profile, and urinalysis prior to treatment can rule out other medical conditions that would make treatment more complicated. It may also detect kidney abnormalities if the bladder has become herniated and resulted in urinary obstruction.

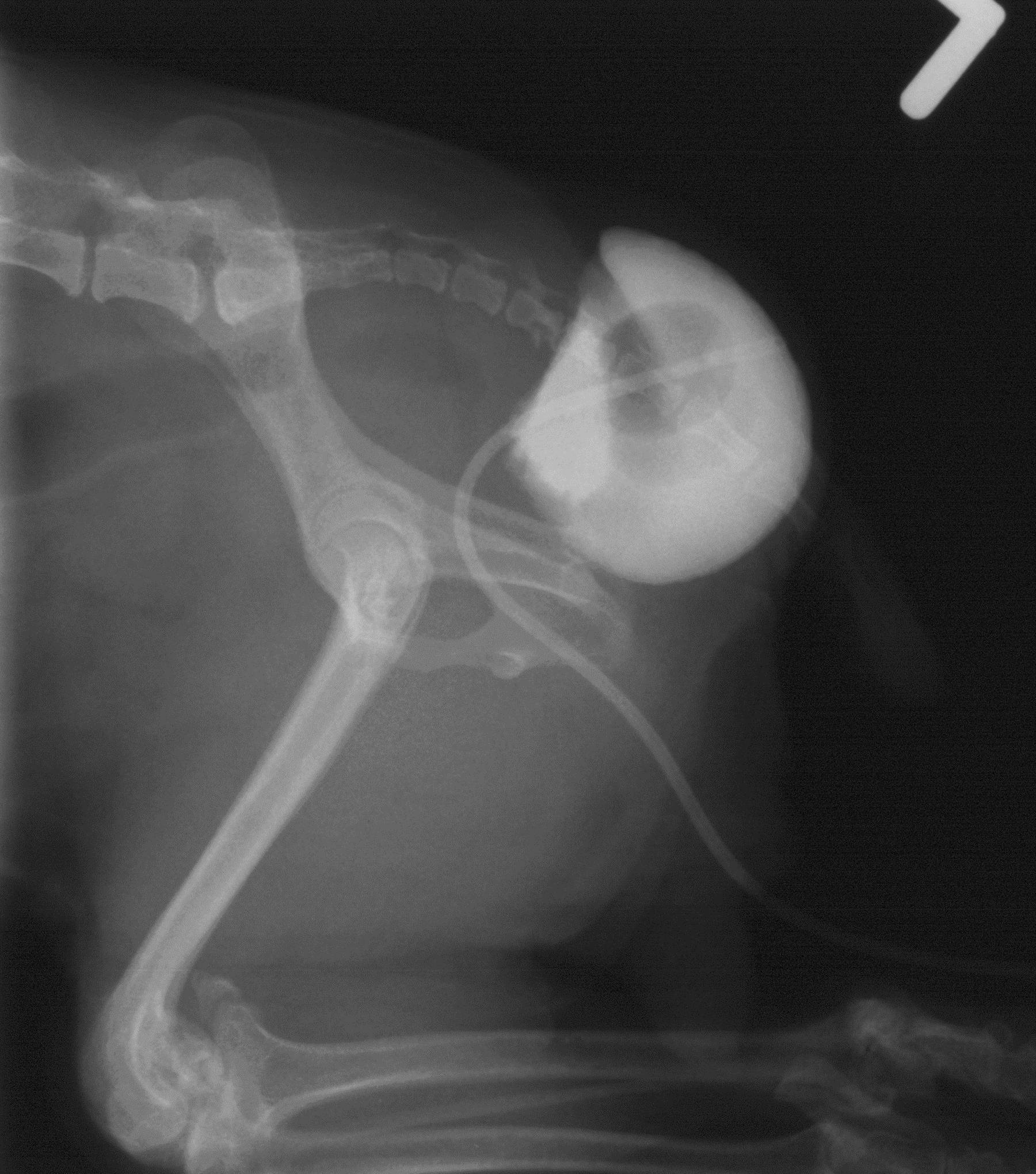

Radiographs or ultrasound can determine what has herniated through the perineal muscle and better screen for prostate disease and other abdominal or pelvic diseases. Rarely, abdominal testicles may be located with ultrasound if your dog appears neutered but is not. Your veterinarian may recommend hormonal testing if there is a question regarding whether your dog is neutered.

How is a perineal hernia treated?

Generally, a perineal hernia does not require emergency intervention, but if your dog is acutely sick from an obstructed bladder, he will require catheterization of the bladder to allow normal urination along with supportive care, including intravenous fluids. If constipation is severe, your dog may require manual removal of feces while under sedation. Stool softeners and special diets can be used to reduce further episodes of constipation while waiting for surgery or if surgery cannot be performed. Any contributors to straining such as prostate infection should be treated appropriately.

The most successful treatment of a perineal hernia is the surgical correction of the muscle defect. Simple hernias can be repaired externally but more complicated hernias may require abdominal surgery to reposition the herniated organs and suture them in place to prevent them from becoming herniated again. A mesh implant to support the surrounding muscles may be needed in severe herniation or if repeat surgery is required.

Neutering is recommended at the same time as the hernia repair, as well as treatment for any other identified causes of straining to prevent a recurrence. Dogs that are not neutered at the time of hernia surgery are almost three times more likely to re-herniate.

As hernias are often bilateral, a second surgery is usually required to repair the less affected side.

What is the prognosis?

With effective surgical intervention, the prognosis is very good. Although there is a risk of recurrence, controlling the straining and neutering of affected dogs significantly reduces this risk. Uncommon complications of surgery include infection and incision breakdown, fecal incontinence, and sciatic nerve compromise. As surgery can be technically challenging, referral to a board-certified surgery specialist is often recommended.

If the patient does not receive surgical treatment, if appropriate surgical techniques fail, or if the cause of straining cannot be treated, the prognosis may be more guarded.