Inguinal Hernia Repair

What is an inguinal hernia?

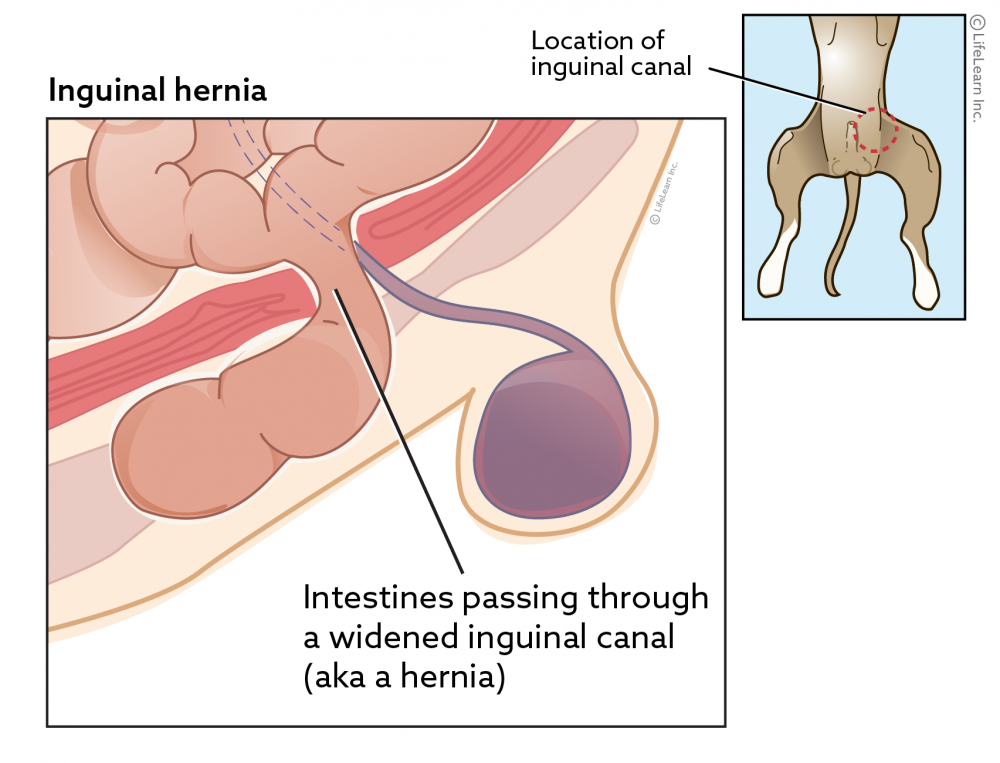

A hernia occurs when a body part or internal organ protrudes through the wall of muscle or tissue meant to contain it. In the case of an inguinal hernia, these internal organs or structures have managed to make their way through the inguinal ring (an opening in the abdominal wall near the pelvis) to protrude into the groin area.

The condition itself can be broadly classified as either acquired (occurred later in life, possibly due to muscle weakness or trauma) or congenital (meaning the pet was born with the condition). Inguinal hernias are uncommon in cats.

Are certain dogs more likely to have an inguinal hernia?

Acquired hernias are more common in middle-aged and older intact female toy breed dogs. Females seem predisposed for the following reasons:

- They have a shorter, wider inguinal canal

- The effect of sex hormones (estrogen) can weaken the collagen in the connective tissues in this area

- The weight of a pregnant uterus or excess fat due to obesity may stretch a weakened inguinal ring.

Certain metabolic conditions, such as excess glucocorticoids in the system (either due to disease or to administration as part of disease treatment), can also weaken the abdominal wall.

Rarely, inguinal hernias may occur secondary to trauma in dogs of any age or sex. This causes disruption and weakening of the caudal abdominal muscles; it is often accompanied by other hernias in the area.

What are the clinical signs of an inguinal hernia?

In general, the first sign of this condition is swelling in the inguinal (groin) area. If only fat or omentum (a mesh-like lattice work that helps nourish and support the intestines) is in the hernia, there generally will be no systemic signs of illness.

If abdominal organs become entrapped or strangulated, clinical signs may include abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty urinating, vaginal discharge or bleeding, bruising of the area, lethargy, and depression.

How are inguinal hernias diagnosed?

Your veterinarian may suspect your dog has an inguinal hernia based on a physical examination.

In the case of an uncomplicated inguinal hernia, the swollen area is generally not painful and is soft and/or reducible (able to be pushed back into place). These can be unilateral (one-sided) or bilateral (both sides). Your veterinarian may be able to feel an enlarged inguinal ring in your dog’s groin area.

In the case of a complicated inguinal hernia, there is often a much greater degree of swelling. The mass itself is often firm, cannot be pushed back into the abdomen, and is painful. The overlying skin is also often bruised and/or reddened.

Some conditions may mimic an inguinal hernia, including an abscess, swollen lymph nodes in the area, a mammary tumor, a lipoma (an abnormal growth of fat), the inguinal fat pad (a normal pad of fat found in the area), and mastitis (inflamed mammary glands). To help confirm the presence of an inguinal hernia, your veterinarian may perform one or more of the following tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to see if there is an elevated white blood cell count associated with intestinal strangulation

- Biochemical panel to look for electrolyte imbalances

- Fine needle aspiration (FNA) to sample the contents of the swelling (generally best done with guided ultrasound)

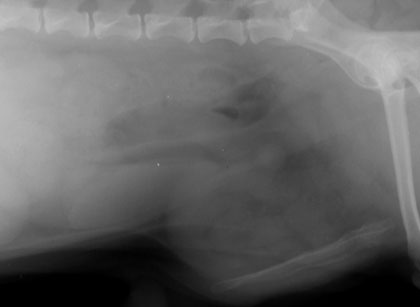

- Radiographs (X-rays), sometimes using a contrast medium, to see if there are abdominal contents within the hernia

- Abdominal ultrasound to determine the contents of the swelling

- Advanced imaging techniques such as Computerized Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

How are inguinal hernias treated?

In general, it is best to surgically repair an inguinal hernia at the time of diagnosis, as delaying can result in a more complicated and difficult procedure. Surgery is required immediately if there is evidence of the bladder, intestinal contents, or uterus trapped in the hernia. Peritonitis (inflammation of the abdominal cavity) or severe pain also indicates the need for immediate surgery.